No. Dementia Minecraft is not the future of video games.

Oasis is a video game created using generative artificial intelligence. It’s a ripoff of Minecraft and its name is a rip off of The Oasis from Ready Player One, itself not the most original of texts.

Trained on footage of Minecraft, Oasis attempts to replicate that game but, because it doesn’t have object permanence, it only really succeeds at replicating the feeling of dementia. In the hands of capable game designers this technology could power a devastating art game about the syndrome. But Oasis is developed by hubristic tech bros who think it’s “a glimpse into the future”.

Despite requiring a $40,000 graphics card to approximate a video game that came out in 2009, it only renders at 360p. Its creators claim that it runs at 20 frames per second. That was not my experience. It’s blurry and slow, unstable and imprecise.

Playing it feels like dying. Indeed at one point during my play session, I looked up at the clouds. Then, I looked down at my feet and realised I had floated up into them. This happened because the game is fundamentally incapable of understanding the relation of objects in space. It’s a three dimensional hallucination derived from two dimensions of source data. Like its creators, it handwaves away what it doesn’t understand.

I have nothing against hallucinations. I’ve dabbled. But I’m not bold enough to pretend the things that I see when I hallucinate are going to put Shigeru Miyamoto out of a job.

There’s an iconic jumpscare in the video game BioShock. The developers pile a bunch of goodies onto a desk in a dentist’s office. They know you'll take a moment to grab these items. So, they use that time to spawn a bloodthirsty, wrench wielding dentist right behind you. Take your time: he won’t bludgeon you until you turn around.

This scare works well because its designers know where you’re looking. They can thus conjure a monster in your blindspot. Not only do AI games not know where you’re looking, they have no designers, and no concept of “where” at all. AI games might be horrifying, but not intentionally so.

“Dementia Minecraft” is apt description of Oasis. It also fits the AI tech bro subculture that created it. These men are desperate to craft… something, but all they can think to do is repurpose the work of others. Their output is forgettable slop, fed to the many in order to build the fortunes of the few.

If you’re reading this then, while these artless vampires might annoy you, they’re not really a threat to you. You have critical faculties. You’ve already played a good video game and have no intention of playing their bad ones.

The demographic that this stuff is a threat to, is children. Right now, millions of under-supervised kids are being algorithmically force-fed AI-generated junk online. We owe their developing brains far more stimulating and challenging art. To deliver this, we must change how our creative industries work.

There are two reasons that our creative industries are producing more and more derivative slop. The first is technical: the AI systems deployed increasingly in creative workflows are inherently derivative. They were trained on what came before them and, fundamentally, all they’re capable of doing is reassembling that training data.

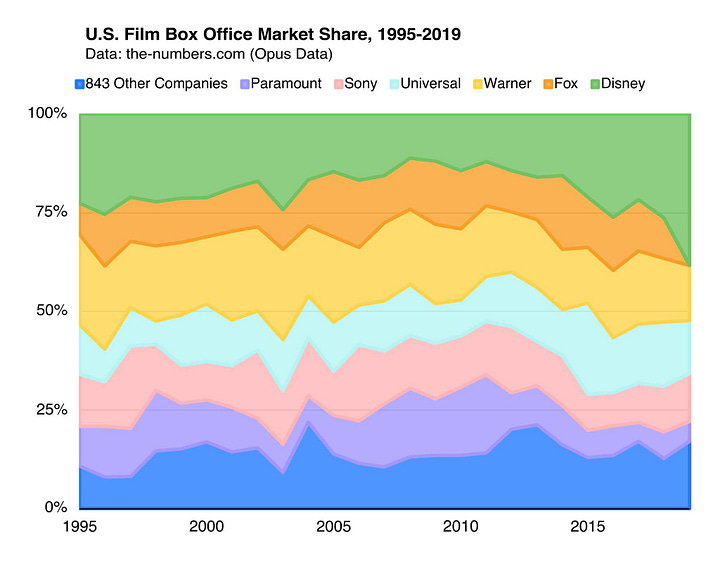

The second reason is capitalism. Or, more specifically, what capitalists tend to do when their rate of profit is declining. They stick together, reducing risk and maximizing efficiency at all costs. This setup, where a small number of companies dominate the market, is called oligopoly. It discourages competition and thus, innovation.

Oligopolists use every tool at their disposal to defend their entrenched power. Their lobbying spend, for example, has increased by around 400% since the year 2000. They also take on debt in order to make fewer texts for more money. This makes it prohibitively expensive for newcomers to compete. And, when a newcomer succeeds in spite of this, they simply acquire them.

Oligopoly encourages cartel formation. In the creative industries this instinct manifests as joint ventures:

Hulu was founded as a joint venture between News Corp and NBC Universal. Comcast, Warner, Providence Equity and Disney also got involved.

The CW is named after its co-founders: CBS & Warner.

MGM+ is a joint venture between MGM, Lionsgate, and Paramount, with Amazon getting involved later.

Vevo is a joint venture between Universal, Sony and EMI, partnered with Warner.

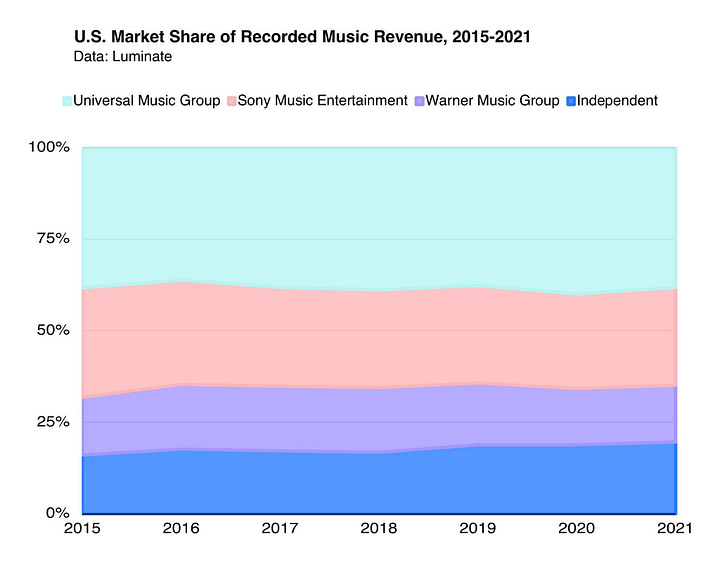

This level of consolidation has led to conflicts of interest that harm creative workers and their creative efforts. The record labels that own stakes in streaming services, for instance, are incentivised to allow streamers to rip-off their artists. They profit either way.

Consolidation also empowers oligopolists to dictate favourable distribution terms for their products. Cinemas screening Disney films for example, are contractually obliged to play the film for longer than usual, to hand Disney a higher-than-typical cut, and to screen trailers for other Disney products before the film.

Downstream from joint ventures are joint franchises like The Wizarding World, Terminator, Lego, Spider-Man and James Bond. The Lord of the Rings, whose rights are divvied up between Warner, Amazon, Harper Collins and the Embracer Group, is a particularly interesting example of this. Parties effectively own different periods of fictional time. Amazon can set its TV series in the second age of Middle Earth. This isn’t because J. R. R. Tolkien wrote a novel about that age. It’s because Amazon owns the rights to an appendix that mentions it.

Members of these cartels benefit from every franchise entry. Packed with references to other texts in their monetizable catalog, the output of this system is derivative in the financial sense (an instrument to hedge or exploit risk), as well as qualitatively. To quote Andrew deWaard:

The demands of derivative media produce travelogs, not so much of urban space, but of networked, financialized, and intertextual time and space.

Contemporary popular media texts now function as risk-hedging derivatives through which capital accumulates in diversified cultural hedge funds operated by a handful of transnational media corporations, disciplined by even bigger financial firms.

The late Time Warner chairman Gerald Levin was a tad more concise when he said:

Space Jam isn’t a movie, it’s a marketing event.

Sequels, reboots, remakes, songs that remake old songs and now games the hallucinate old games. These are all symptoms of the capital consolidation outlined above.

None of this should be read as nostalgic. There was no golden age. Creatives have always had to struggle for control, compensation and conditions. I also don’t mean to imply that derivative media inherently sucks.

My point is that media, and the conditions of its production, are heavily shaped by abstract financial processes and long-term trends in political economy. We could have a vibrant media landscape with diverse stories and fair jobs. Instead, we’re stuck in a greedy, extractive content machine.

If we want to control the long-term trajectory of our mediated lives then understanding these processes, and whose interests they serve, is vital. But what can we do about this?

Legislate

New tax laws, changes capital gains, carried interest, executive pay, stock buybacks and antitrust rules could reform the financial sector. This would in turn, reform the media sector which, it’s important to understand, is shaped and distorted by financialization.

To reform the media sector directly, AI companies must be made to pay for the media they use to train their models. OpenAI reckon that “it would be impossible to train today’s leading AI models without using copyrighted materials.” To which I would respond: that sounds like a you problem.

Our governments are currently carving out copyright exemptions for AI developers. Students, cultural workers, policymakers, fans who are dismayed at the way things are run, and really anybody who cares deeply about the media must oppose this.

Our governments could break up the conglomerates. They could also separate entertainment giants from asset managers if they wanted to. The problem is that industry spends enormous sums to make sure that won’t happen. You would be right to point out that Starmer is in Number 10, Trump is in the White House, and anti-monopolist Lina Khan no longer chairs the Federal Trade Commission. We are losing influence, and we need to win it back if we have any hope of legislating. We need to win the argument.

While we talk about tactics, it's important to notice an interesting tension here. The interests of our enemies are not aligned. The old cartels want to lock-in their gains. Meanwhile, the new wave of AI tech bros aim to flood the zone with endless AI-generated copies of the cartels’ intellectual property.

Disarming one of these groups without inadvertently empowering the other is going to be a balancing act. Perhaps, while our enemies fight each other, we should spend our time building platforms and production processes outside of their control?

Educate

I was a film student and now I work as a game developer. Looking back on my media education, I see that I didn’t learn enough about how financialisation would impact my work. I had to develop financial literacy to understand what was happening to my industry. To advocate these reforms, and to imagine a fairer future. Media educators must help the next generation of creatives gain these skills before they start working. They shouldn't have to learn them on the job.

Film, television, music, and games matter to everyone, no matter their politics. So, the media system offers a unique political opportunity. Connecting the rise of finance to the decline of culture could make for a strategically successful association.

Organise

Defending and extending media unionisation is vital, as evidenced by recent Writers Guild of America strike action wins. A key first step here would be to win the right to collective bargaining for all creative workers.

Musicians, for example, are currently barred from organising. This puts them at a disadvantage when negotiating. The record labels are collectively organised, in that they all hold equity stakes in stingey streaming services. As a result, record labels have a compelling financial incentive for accepting low royalty rates for their artists, and those artists are legally barred from fighting back. We need to level this playing field.

Conclusion

My view is that none of this is likely to happen. The entertainment and finance industries spend a lot of money to get special treatment. This often leads to unfair treatment for everyone else.

If a lifetime of media consumption has taught me anything though, it’s that audiences like a happy ending. So I’ll leave you with the words of screenwriter Zack Stentz:

Hollywood is based on giving audiences what they might not know [they want]. Any attempt to drive risk out of that process is sooner or later doomed to failure.

Acknowledgements

This article covers AI and financialisation, linked by the idea of derivative media.

The AI part of the article was inspired by TRASHFUTURE episode 852 (Spotify, YouTube, Apple).

This is where I first heard the term Dementia Minecraft.

I became interested in the financialisation of media after listening to episode 189 of American Prestige (Spotify, YouTube, Apple). This episode features Andrew deWaard, whose words and graphs feature heavily in the back half of this article.

His book Derivative Media: How Wall Street Devours Culture, is free to read.

![url_upload_678f58dd99c54.gif [crop output image] url_upload_678f58dd99c54.gif [crop output image]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!f8Q-!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_lossy/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F39f6fc11-a32c-42ab-8a44-6b0631ff0aa6_1870x869.gif)